My name is Josh Ventura. I am a software developer with a focus on compiler design and game development. I graduated from Ashland High School in 2010, and received a BS in Computer Science and Engineering from The Ohio State University in 2013.

Basics about me: stuff I'm into, stuff I'm proud of, stuff that happened. Mouse over/long tap for context.

Born

January 15, in Ohio. I don't remember much about being a baby, though I'm sure my mother would have all kinds of fascinating things to tell the world about it.

Video Games

Video games are a huge part of my life. I started gaming when I was about five years old, and I'm unlikely to ever stop.

School

I attended public school like everyone else. School shaped my day to day schedule, and had a couple other side effects on my early life.

Collections

I collected rocks and coins and various knick-knacks as a kid. My father built me a treasure chest to keep some of it in. Actual minerals had their own boxes, while the treasure chest accumulated costume jewelry, spray-painted stones, and chunks of tin foil.

NES

A couple NES consoles had been handed down through my family, and I ended up with one of them. I played a lot with my cousin, Allison, and a little bit on my own or with Bryant.

Kindergarten

Kindergarten was a great year for me. My mother joined in as a TA for my class, so I felt very much at home. Kindergarten was done in half-days, so it didn't eat very much of my life, either. When summer vacation hit, I mostly missed my friends. My mom networked with the other moms and made sure I had friends. One of those friends, Bryant, fueled my love of video games, lending me his copy of Kirby's Adventure.

Rocks

My father had a number of small geodes around the house, along with chunks of pyrite and wedges of tiger's eye. Our driveway was gravel, at the time, and I would weed through it to find big deposits of calcite. Young me thought there might be more geodes hiding away in the limestone.

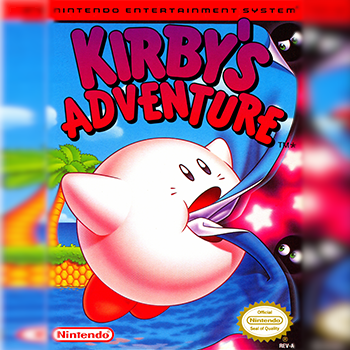

Kirby's Adventure

I wasn't very good at Mario, and only ever cheated at Duck Hunt, but Kirby's Adventure was slow-paced, manageable, and fascinating to me. It was mind-blowing that it worked, but being that I was only around five years old, the oddest thing to me was the strange analog distortion in the top-left corner of the screen. Video games were magic, and this was like a tear in the fabric of that magical universe.

Collecting pieces of a mythical star rod, taking magical doors throughout space, using a sampling of powers from a palette of size unknowable to a five-year-old... these concepts were magic. The fact that a video game defied the rules of this universe while making up its own fascinated me. My mother really didn't care for my fascination with games, and my father really didn't understand it, but they let it develop and fueled it monetarily.

SNES

Toward the end of first grade, my uncle gave me a Super Nintendo, and I played the hell out of Super Mario World.

First Grade

Come first grade, I was on my own in school, but my parents kept a close eye on me and had already set me up for success. I was a curious child, and my dad answered every question I had for him. My personal learning was further fueled by access to computer games like KidPix and some long-forgotten maze game wherein you had to solve math problems to unlock doors. Some of the math was beyond first grade, so I had to learn it.

Super Mario World

The game was fantastic, especially compared to its NES predecessor. The ability to save game progress and the variety of levels really makes a difference, especially to a kid. Video games were becoming bigger and more magnificent; the secrets in the game drew me in, but kept me distracted from the bigger picture of beating the game. This wouldn't be the case for long.

N64

Some time in second grade, or so—not very long after he gave me the SNES—that same uncle passed me his N64, along with Super Mario 64. The controls were shaky, and the graphics were pretty bad, but it was easy to get lost in the game. My parents had thus far been inclined to avoid video games, or at least they did not normally buy me any, and I didn't ask. This wouldn't be the case for much longer.

Second Grade

Second grade was miserable for me. The teacher didn't really like me, school was starting to become more demanding and less fun, and I really just wasn't feeling it. Before second grade, the teachers made school engaging enough that it kept my interest. When that stopped being the case, they wanted to put me on some ADHD drugs. Fortunately, my parents knew better, and they let me coast through second grade to greener pastures.

State Quarters

Toward the end of first grade, the US Mint started circulating quarters for each state. My father bought a booklet containing a map of the US with a special slot for each state's quarter. This led to an interesting incident with my second grade teacher, but, again, parents to the rescue.

GCN

Come third grade, Nintendo released the GameCube. Derek was quick to own one, and happy to share with me. The launch title, Super Mario Sunshine, had comparatively incredible graphics, smooth controls, well-honed gameplay. Once again, the capabilities of video game consoles seemed endless.

After Derek got a GameCube, I asked my parents for one, and they went out and got it for me with very little protest. I think they were happy I was interested in something. The GameCube itself was a great platform, but it was just a conduit for the pieces of software that actually changed my life.

Third Grade

As miserable as second grade was, third grade turned it around. My teacher liked me and seemed to genuinely care about me. She worked to figure out how I thought and she tried to keep me interested in school. I was still a messy person, and I never grew out of that, but she made it manageable. I went from being the ADHD candidate to the gifted program candidate, and by the end of the year, I was enrolled in a program called "Search."

Bryant and I had sort of drifted apart in second grade, but in third grade, I made a new friend who really changed my life. Derek was frequently the first kid on the block to own the latest games, and when I'd come over, we would play them together, or I'd just watch him play. He eventually inspired me to ask my parents for new games, like Paper Mario, and new consoles... like the Game Cube.

Action Replay

One day, Derek called me up and told me about something new he bought: a device called an Action Replay. When he told me he was making Mario fly around the game, I didn't really believe him; I assumed he was pulling a joke or that the game was having some weird glitch. When he showed me, that is when my perception of video games began to change.

Within a few weeks, I bought my own Action Replay, and began trying it out. It was unbelievable; all you do is enter some "codes" into the device and you can change the game's entire reality. I was astonished. Derek told me you could get more codes online, and so my 56K and I did just that. But then I started to wonder... What made the codes work? And so began my whirlwind tour of computer science and cryptography.

Fourth Grade

Fourth grade was another change of pace. This time, I would have two teachers—one for math and sciences, and one for reading and social studies. Another point of difference: the math program would be largely operated by computer, and otherwise self-directed. We graded our own work and led our own studies. It was consequently somewhat competitive, and I would often stay in from recess to get ahead on it. Derek was naturally better at just cranking out solutions to math problems he understood; he inspired me to push myself to learn more math and get good at the math I knew.

Reverse Engineering

It turns out that Action Replay codes were specially-encrypted DWords, where the first three bytes gave the address in the GameCube's tiny memory, and the next byte gave the new value to assign. I quickly learned to work with hexadecimal numbers, and how games functioned internally. The vendor, Datel, used encryption to prevent homebrew code development, but their scheme was quickly broken by a resident programmer, Parasyte, whom I came to look up to.

It was then that I decided I wanted to become a programmer. I downloaded a copy of what I guess was GCC, because I was going to learn C, just like Parasyte. This wasn't to be. Unable to find an IDE in the mess of nonsensically-named binaries I had downloaded, I elected to try other venues. Eventually, I went directly to finding how to make games.

Fifth Grade

Back to the single-teacher structure. My fifth-grade teacher knew so much about so many things, and was happy to teach us. She was one of those teachers who made sure that advanced students could really learn a lot about the world while the other students were learning the required material. She taught the class about basic circuitry, magnetic fields, biology, anatomy... we built a telegraph, sat down and tried to figure out how a siphon-based water multiplying machine worked, build electromagnets, dissected pig brains, cow eyeballs, and pig lungs... Mrs. Weaver was one of the single most influential people in my life. And when I wasn't in school learning around the curriculum, I was at home learning about computer science and occult mathematics.

RPG Maker

Leaving GCC for something an 11-year-old would be more able to understand, I stumbled upon RPG maker. I began immediately learning its custom flavor of script, reading manuals included with the release. I learned how to assign variables, how to print variables, then basic control flow. There were, to my recollection, no for loops. It is possible I missed for loops, but I never used them with RPG Maker. It was fun to write little text-based games in the script, but I could never get a standalone executable of any sort to compile with the toolkit, and so eventually, I gave up, and went to look for another toolkit.

Game Maker

The next kit I found was Game Maker, a program written by a computer science professor in the Netherlands. I obtained his newest release, Game Maker 5, and gave it a quick look-over. My first impression was that it was a downgrade; I noticed the "Sprites" folder and lamented that I had left RPG Maker specifically to avoid making games about fairies and magic. I hemmed and hawed for a few days, but eventually decided to give the Game Maker manual a read. I quickly learned that sprites had nothing to do with magic or fairies, and began reading through his manual cover to cover.

By sixth grade, I had made my first game. From a code quality standpoint, it was awful. From a physics standpoint, it was bad; gravity was replaced with an inversion of vertical speed after jumping a certain height. That said, the game as a whole was quite imaginative, and rich with platform elements. In retrospect, it was a pretty good first game.

Game Maker was really something special. It allowed me to express some very cool ideas in the form of interactive games or procedural animations. I got the most fun out of writing small, interesting game elements as opposed to following through to complete a whole game. I learned many amazing graphical techniques, and played around implementing dozens of genuinely fascinating game elements. I loved every minute of it.

Sixth Grade/Middle School

Sixth Grade was not part of Middle School in my district; Middle School was seventh and eighth grade. But these years of my life were less formative and more informative. What I learned most from my sixth-grade teachers (particularly my math/science teacher) was that teachers are humans, too. Sixth grade was when I started to see the world for what it was.

The Yoyo Inquisition

My game development career would continue with Game Maker until a few months after my fifteenth birthday. By that time, I had gleaned a firm understanding of what programming actually involved, but had little knowledge of the tools, languages, and algorithms that powered my use of Game Maker. I decided that my last act as a Game Maker user would be to construct a big, polished game, based loosely on Kirby: Canvas Curse. This continued quite effectively for a while, but it was around this time that a company called Yoyo Games moved in to take over the development of Game Maker. They entered with a wake of extreme unprofessionalism and poor coordination; they conducted themselves in a way that made them seem extremely unofficial. Even Dr. Overmars had presented a better illusion of Game Maker as a respectable product, but then, I was quite young throughout the bulk of that.

It wasn't long before my Game Maker enthusiast friends and I grew angry at Yoyo for their combination of corporate antics and their inability to effectively run the Game Maker project themselves. I was happy to chime in with suggestions, but these suggestions were largely ignored or dismissed. One of these suggestions was a compression tool which snipped off the binaries used by Game Maker games for distribution, and then reattached them client-side for play. I elected to enact this suggestion on my own, and was met with opposition similar to what GMBed received. GMBed was a project run by members of the G-Java team which could run Game Maker games in a browser. The Yoyo EULA had something to say about both of these projects. When confronted, a staff member ensured me that they would be doing something "similar" on their own, which I took to mean "we're gonna do whatever we like with your ideas; cheers."

Eventually, I became completely fed up with Yoyo, personally. Ceasing all of my own game development, I shifted my focus to implementing one of the other ideas I had offered. This idea grew into ENIGMA, a project I operated throughout the rest of high school and into college.

High School

High school was a thing that happened. I mostly kept to myself. I got along with other students, and my high school was a generally peaceful place to be, but I didn't involve myself any more than I had to... with a couple exceptions.

I joined the high school newspaper team, which was a reasonably rigorous program. I didn't really realize what I was signing up for; I only signed on because it counted as an English credit, and after my Honors English 10 teacher utterly ruined reading, writing, and liberal arts at large for me, I would have taken any class to avoid taking another literature class.

Math was one subject I always benefited from, and my Calculus teacher was the best in the country. The organization behind the material she taught us was unparalleled. She brought in models to illustrate things visually, called back to concepts we had learned earlier to show us how everything fits together... then to top it all off, she didn't make us do homework if we kept up our grades. Basically, she did everything required to make it take zero effort for me to learn calculus, which gave me more time to focus on my own learning at home.

ENIGMA

With Game Maker no longer meeting my needs, and Yoyo on my shit list, I turned my attention to learning C++. On my journey, I found myself writing helper methods that resembled Game Maker's library. It occurred to me that a lot of what I was doing in Game Maker could be done verbatim in C++.

I had earlier suggested on the Game Maker forums that it would be possible to compile GML (Game Maker Language) like a real language; seeing how C++ constructs could be used to turn GML into valid C++ with very little, very regular modifications, I decided to attempt to do so myself.

At that point, I essentially declared war on Yoyo. Still being more familiar with GML, I began a project in Game Maker itself to translate GML code into C++ code. When I was done, the project would simply be used to translate itself, bootstrapping a compiler in a proper language. This would be my first experience with large-scale refactors and technical debt.

As the project grew, so did my understanding of the nitty-gritty of game making techniques and my technical knowledge of C++. Long after I had smoothed my self-translated compiler into an actual C++ application, the requirements of that application continued to grow. Simple maintenance problems became evident with the scale of the project. Cross-platform support became a highly-demanded feature. ENIGMA required me to learn dozens of new frameworks and work competently with a new operating system.